Author’s note: This is a bit of a screed against this thing some call ‘arterials’. I dislike them both when they go through old urban areas of cities (circa 1950s), and the arterials that were built in the 70s, and the arterials that keep getting built/expanded today. Arterials are all forms of dangerous, inefficient, wasteful, and promotive of dangerous systems/interactions. They squelch all sorts of healthy things that could be existing, in the same way that pouring agent orange might squelch health from an ecosystem.

I complain about the bad to the degree it’s blocking progress on the good, and actively causing harm. There are thousands of people killed per year in America on dangerous roads, and the health/wellbeing effects of what these roads do to communities sociologically is endless. The ‘cost’ of giving up the regime of euclidean zoning & arterials (and the preconditional acceptance of domination and supremacy) is to then participate/observe/witness the problem-solving efforts and experiential opportunities that arise when various steps of amelioration are achieved. Parks. Courts. Playgrounds. Street furniture. ‘pedestrian boulevards’. Food trucks. night life. street life. peacefulness and silence. beauty. safety. life. pickleball. benches. cafes. novelty. interestingness.

Previously, part 1: Parking Minimums as Ethnic Cleansing, part 2: Setbacks as Ethnic Cleansing, part 3: 35' Height Restrictions as Ethnic Cleansing.

For parts 1, 2, and 3, I’ve talked about concepts that would be familiar to those knowledgable about land-use law in America. query, and get to the other side of the coin, when it comes to ‘euclidean, form-based, restricted-use’ zoning.

We’re talking about arterials today. Arterials are the lifeblood (heh) of urban road networks.

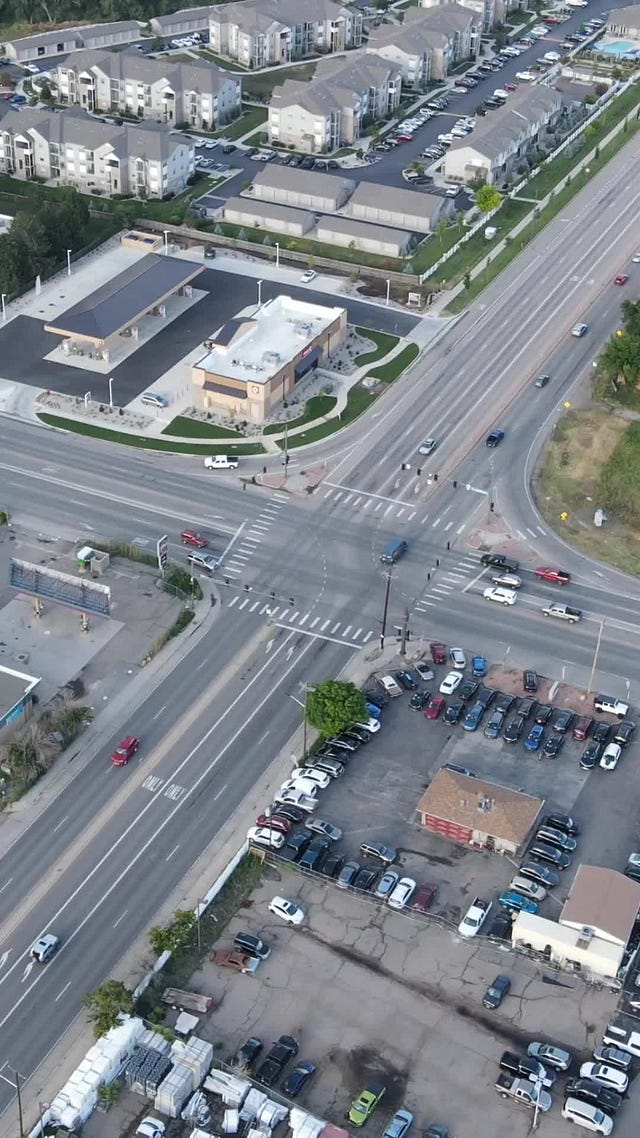

Here’s what an utterly banal arterial looks like:

You can barely see the person on the bike on the left, hidden behind the sign. What an apt depiction of an arterial. Note the sidewalks. A ‘detached sidewalk’ on the right, an ‘attached sidewalk’ on the left. Big-box retail, a park. Crosswalks.

Every day, most of the miles driven on roads in the USA happen on arterials. The guy that invented them shaped how other cities around the world built their own roads, so the USA isn’t the only place you’ll find arterials, but it is the ‘cradle’ of arterials. (Technically, NYC is the birthplace of this abomination.)

Here’s what a ‘modern’ junction between two rural arterials looks like:

Tiktok failed to load.

Tiktok failed to load.Enable 3rd party cookies or use another browser

Why are arterials “so bad”?

A few layers. I don’t have time or patience or gentleness to express this differently:

Arterials are dangerous for all participants, from a ‘physics and collision’ point of view. Car accidents are common, as are ‘pedestrian fatalities’.

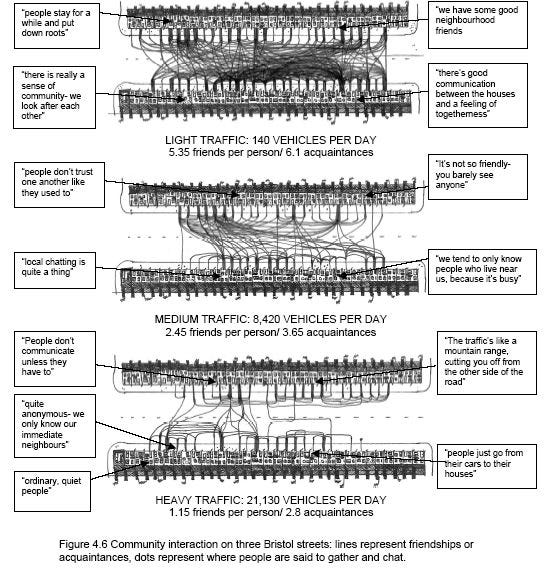

Arterials serve as walls, bisecting the landscape. Enough intersecting arterials feels like having walls all around you.

Arterials are expensive to build

Arterials are expensive to maintain, for example to keep clear of snow after it snows, and to repair potholes, damaged curbs, lights, and more.

Arterials represent a mix of ‘flat earth’-ism, and conspicuous consumption

Arterials are the ying to the single-family-neighborhood yang.

Arterials generate horrific noise, spreading the noise across square miles of territory. That noise is definitionally akin to intrusive thoughts, but (in my opinion) often far worse and spread everywhere. I will expand on the noise issue of these roads in a future episode.

Arterials cause many, many people to wait in line, and then race through a narrow gap in time and space, and then wait in line again. This waiting/racing push/pull dynamic creates waste of all kinds, and creates dangerous conditions as a matter of routine operations.

As soon as it’s night time, or raining, or snowing, it often becomes very difficult to ensure adequate safety for anyone near an arterials.

Car accidents. They’re horrible. If you have people you love, and they travel along or across arterials, you’d be forgiven for feeling some anxiety on their behalf:

I’ve got beef with ‘urban arterials’ and ‘rural arterials’. I grant the moral authority of neither.

Imagine how some evil people in the 1950’s, seeking to solve their ‘ethnic enclave’ problem, might attack a population:

I’ve marked out arterials in green, of course 6th ave and I-25, which are not marked in green, are also are utterly uncrossable.

Most of the area in the picture has been historically hispanic neighborhoods in Denver, and Denver municipal staff, with support of other white people in Denver, have consequentially built arterials through the areas, serving as walls and destructive influences.

Note the industrial zones to the east/right side of the neighborhoods. The Color of Law talks about how planning staff would fence off ethnic neighborhoods with industrial zones, to ‘prevent the spread’ of those undesirable influences.

takes deep breath.

Now, remember, these arterials serve as walls which sever community connections, of course, but they also funnel such harm and sadness into the environment around them. They are loud, smelly, dangerous, cacophonous, illness-inducing. Depressing, degrading.

Tomorrow, “we” could go out and start using cones to slim arterials down to one lane in each direction, with each junction mediated not by traffic lights and stop signs but by traffic circles.

Here’s what that traffic circle could look like. Currently the city engineering office is claiming that it’ll take two years and half a million dollars to ‘fix’ this intersection by adding a traffic light.

Here’s how I might replace this uncontrolled intersection with a roundabout. Simply use traffic cones or traffic posts to ‘scribe out’ these shapes on the ground. I’d add some bump-outs for non-vehicle traffic at the four corners, and it would be done:

It would take so little time and money to convert each intersection.

A few of these dotted about, and as drivers enter the ‘zone’ of traffic circles, their norms for driving will change, they’ll go a bit slower, and, critically, the whole avenue becomes better:

The modifications would be temporary, of course - they’d need to be modified and iterated on a bit to make sure the shape and configuration is right. This simple process takes a few traffic cones and an hour or two to test the design, and then the cones can be left. In my testing, they’ll sometimes remain undisturbed for weeks.

You can already see that there would be repetition in the traffic circles, and once a good pattern was picked for the wedge-shaped spaces and the circles themselves, they could easily be spread across a bunch of intersections, and everyone would figure out quickly how they work.

If one looks at land-use laws from the lens of ‘control’, one wouldn’t look long at the maps without thinking about how people get around. There’s ways to benefit, from how people get around, sure, but critically, controlling how ‘people get around’ is quite close to ‘preventing them from caring for themselves’.

A quick gander through The Slaughter of Cities and The Color of Law, might be worth a few of your hours.

Anyway, once you have eyes to see, it is horrifying, truly, how much of the square meters of a settled region is dedicated to the ‘land use pattern constraint’ of single-family housing.

I see a lot of it when I fly my drone around, of course, but most single-family housing in america is so boring it’s not even worth recording. If I did, I’d have a channel full of boring videos like the second half of this video:

Tiktok failed to load.

Tiktok failed to load.Enable 3rd party cookies or use another browser

But I spend a lot of time, and so do you, dealing with these things called ‘arterials’.

Do you know what this is? What an arterial is? Do you know which roads are defined as arterials, and when you’re driving on one, are you confident that you are (or are not) on a stretch of asphalt designated as ‘an arterial’?

Some people, if I asked “do you know what an arterial is?”, would be offended. Others, normal people, and especially non-native english speakers, if you use ‘arterial’ you’ll realize it’s jargon, and in defining it carefully, you’ll get a sense that the word itself is a slippery little beast.

This is a tricky article to write about, because so much of what matters about ‘an arterial’ is the experience of one. And not just the experience of it once, but the experience of it as if you lived near enough to one that its presence exerts a pressure on your life.

The problems of analogy, and why ‘arterial’ is closer to mis-direction than something appropriately descriptive.

What do you think of, when you hear the word ‘arterial’. Especially if it’s unfamiliar to you.

It’s an artery. It’s critical. It moves blood! It’s next to the heart! If it’s blocked, it’s bad.

This sense of ‘needfulness’ pervades discussions around what roads do and don’t qualify as arterials, and what should be done when the ‘problems’ of arterials begin to manifest. Here’s how the government itself reports on arterials.

Arterial roads have diverse manifestations. They include rural and urban roads and roads with two to 10 lanes, and they may carry between 2000 and 55 000 vehicles per day. In 2011, arterials accounted for between 25% and 73% of all vehicle miles traveled in the United States; the range of this estimate illustrates the difficulty in classifying these roads.2 Despite their heterogeneity, the field of transportation has generally defined arterials near the top of the hierarchy of streets because they mediate traffic flows between local streets and larger freeways.

In the same way as ‘single family housing’ dominates the built environment, arterials dominate the ‘transportation environment’. They might be up to TEN LANES WIDE, carry up to 55,000 vehicles/day, depending on how you count them the are responsible for almost 3/4ths of vehicle miles travelled in the USA?

Arterials are the dark matter of the american way of being.

Arterials limit mobility. They have a cost associated, that’s illegible to the planners, and that’s ‘arterials as walls’.

Arterials function as walls in two ways:

the arterial as a wall between crossing the street:

the arterial as a wall around a neighborhood of white people, making it hard to get in/around neighborhoods without a car.

Here’s an example of arterials in a suburban area (‘white enclave’), with the red dots and connecting lines showing the path someone would have to travel to move point-to-point:

If you can wall “people” off from each other, you can control (some important aspects of) “them”.

Arterials also impose a certain tax of time. It’s hard to go directly point-to-point in a district defined by arterials. Non-arterials tend to not connect reliably, and the arterial is often clogged with traffic.

That makes it expensive in time, and in well-being. In Denver, I’m intimately familiar with Wadsworth, Federal, Sheridan, Colefax, University, Mississippi, and other arterials. Every time I have to travel along or across one of these roads, that overlap of my journey and an arterial is always where I experience the most misery and danger.

If we didn’t have arterials, what would we have?

Literally anything, but for starters, go look at 32nd ave in Lakewood and Golden. That is what roads can look like that go through wealthy neighborhoods. I don’t actually like 32nd that much, but it’s less dripping in ethnic cleansing than Colefax, so I give it some credit.

Colefax vs. 32nd is the difference between a road used for ethnic cleansing against an ethnic group and class. Colefax looks like a war zone, 32nd is mostly nice and pleasent. They’re parallel, but 32nd goes through a white part of town, while colefax doesn’t, so colefax residents couldn’t resist the pressure that the 32nd ave residents didn’t even have to try to resist, because planners don’t put arterials through white neighborhoods.

When I lived in Golden and commuted (via scooter) to Denver, I had two routes I could take. One was horrible, dangerous, loud, full of racing traffic and stopped traffic, on a road that is sometimes 8 lanes wide, with vehicles crossing it from both directions in ‘controlled’ and ‘uncontrolled’ ways.

The above screenshot shows how frighteningly prevelant arterials are. Those yellow lines are where the road network hurts the city of Denver.

“Arterials”, which have the feel of “almost a highway”, and are usually lined with that distinctively american mix of commerce and industry, grew out of the fact that as suburbs were being built, the people building them liked the look (on paper) and found the form of it convenient.

It became a pattern that lived in a book that others, years and decades later, could pull back out of a book and apply to the built environment. No traffic planner has ever lost their job for suggesting that an arterial be built, or that a non-arterial be re-designated as an arterial, for a variety of plausible-sounding reasons.

It was well-appreciated that having an arterial run through your neighborhood was a death-knell, and as some arterials in some spots grew from two lanes towards ten, that widening was often-enough coercively applied selectively to “troublesome”areas.

Walkable neighborhoods are where it’s at. Property values go up as areas become walkable.

Instead of using a huge intersection with many lanes of traffic waiting for their turn, drop the lanes to one in each direction, off-center the actual intersection, then invite any alternative activity to fill the new space.

Food trucks. Street furniture. Pop-up park. Whatever. It would be insane how much street-space could be re-purposed.

Green lanes are the slimmed-down car channels, yellow lines are the new space that could be reclaimed for alternative uses.

It is an improvement, less people would die on the roads, and it could be safely set up with a few dozen cones, a small crew of three or four people, and an hour.

-Josh

Future episodes:

The Refusal to Abate Vehicle Emissions, Especially Noise as Ethnic Cleansing

The Refusal to Grant the Presence of Harm in Transportation Systems as Ethnic Cleansing

What Else To Do, Part 1: Destinations and Places First

A More Correct Way to Grade Intersection Performance